Chapter 04

Capturing metadata

Note

The code for the entire chapter can be found at the src/chapter_04.3 directory

The Logger is writing to the file as expected, but there is an issue: it is not capturing any useful metadata. Here is an example of what our logs currently look like:

Hello this is a log of type ERROR

This is no different than using the standard console.log method. For example, we could write:

const logger =

/* init logger */

function create_subscription() {

const my_log_message = "This is an error";

logger.error(`[Error]: create_subscription() Line No. 69 ${my_log_message}`);

};

This code appears to work. However, if you add more functionality above this function in the same file, the line number will change again and again, which is not ideal.

For a logging library, it's important to minimize the amount of unnecessary code that clients need to type out. We should do the heavy lifting for our clients, so they only need to call our logger.error (or other similar) method.

This will make our library easier to use and more user-friendly.

function my_deeply_nested_api_route() {

logger.error('my error')

logger.warn('my warning')

}

The output of the above code should look like this:

[2023-08-19T15:10:37.097Z] [ERROR]: my_deeply_nested_api_route (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtar/test.js:12) my error

[2023-08-19T15:10:37.097Z] [ERROR]: my_deeply_nested_api_route /Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtar/test.js:13 my warning

How cool would it be to achieve this functionality with a little bit of Javascript hack?

Before we dive into the details of how we can extract the function name or its line number, let's take a small break to understand what a call stack is. But before we understand what a call stack is, we need to understand what a stack is.

What is a Stack?

A stack is a data structure that is widely used in in programming. It is designed to store a collection of elements and is based on the Last In First Out (LIFO) principle. This means that the most recently added element to the stack is the first one to be removed.

Stacks are used in a variety of applications, from handling function calls to undoing/redoing actions in software applications. Stacks can also be implemented in different ways, such as using arrays or linked lists.

Examples of Stacks

Stacks are a common occurrence in everyday life, and here are some examples:

- A stack of books

- A stack of files

- A stack of pizzas

In each of these cases, the most recent item is placed on top of the stack while the oldest is located at the bottom. For example, to access the pizza at the bottom, you will need to remove all the pizzas above it in the stack.

The Call Stack

A call stack is a special type of stack that keeps track of function calls. Whenever a function is called, its information is pushed onto the call stack. When the function returns, its information is popped off the stack.

Here is an example of a call stack in JavaScript:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

function calculate() {

const x = 10;

const y = 5;

const result1 = add(x, y);

const result2 = multiply(add(1, 2), result1);

return result2;

}

calculate();

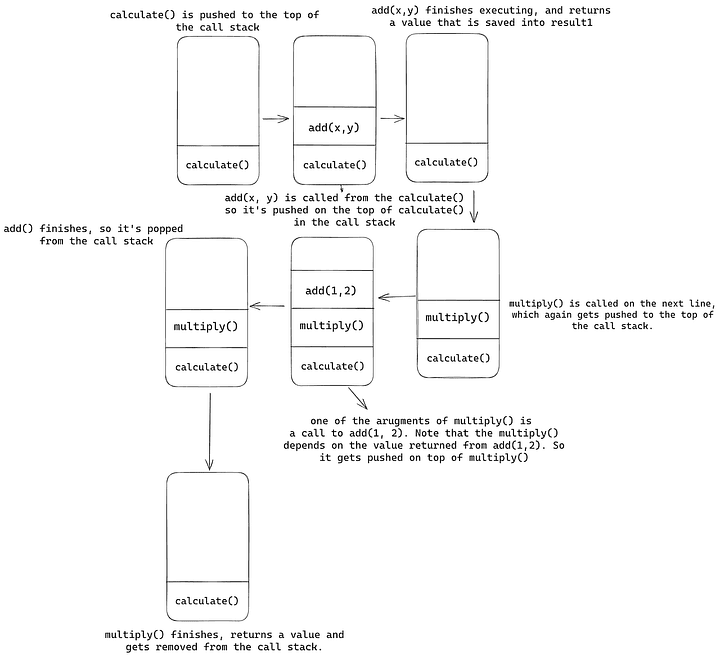

In the example provided, the calculate function calls two other functions (add and multiply). Each time a function is called, its information is added to the call stack. When a function returns, its information is removed from the stack.

To further illustrate this, consider the following graphic:

When the calculate function is called, its information is added to the top of the stack. The function then calls the add function, which adds its information to the top of the stack. The add function then returns, and its information is removed from the stack. The multiply function is then called, and its information is added to the top of the stack.

One important thing to note is, when multiply is called, the first argument is a call to add(1, 2). That means we need to push the add(..) back to the top, above multiply in the call stack. When the add finishes executing, it's removed from the top.

This process continues, with each function call adding its information to the top of the stack and returning, with its information being removed from the stack.

This call stack is important because it allows the program to keep track of where it is in the execution of a program. If a function call is not properly removed from the stack, it can cause a stack overflow error, which can crash the program.

Note

In compiled languages like C++ or Rust, the compiler is smart enough to inline the add() function above, and directly place the contents of the add function in the place of the function call. This can result in performance improvements by eliminating the overhead of a function call and return.

Getting the stack info

How do you even see the stack? Well, it's not that hard. When you throw an error, that error contains the information about the stack.

function main() {

child();

}

function child() {

grand_child();

}

function grand_child() {

throw new Error("This is an error from grand_child()");

}

main();

If you run this file using node your_file_name.js it outputs this on the console

Error: This is an error from grand_child()

at grand_child (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:10:11)

at child (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:6:5)

at main (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:2:5)

at Object.<anonymous> (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:12:1)

at Module._compile (node:internal/modules/cjs/loader:1198:14)

...

We only need to care about the top 5 lines. Rest of those are Node.js's internal mechanism of running and executing the files. Let's go through the error above line by line:

The first line includes the error message

"This is an error from grand_child()", which is the custom message we provided when we used thethrowstatement in thegrand_child()function.The second line of the stack trace indicates that the error originated in the

grand_child()function. The error occurred at line 10, column 11 of thetest.jsfile. This is where thethrowstatement is located within thegrand_child()function. Therefore,grand_childwas at the top of the stack when the error was encountered.The third line shows that the error occurred at line 6, column 5 of the

test.jsfile. This line pinpoints where thegrand_child()function is called within thechild()function. That means,child()was the second top function on the call stack, belowgrand_child().The fourth lines tells us that the

child()function was called from within themain()function. The error occurred at line 2, column 5 of thetest.jsfile.The line 5th tells that the

main()function was called from the top-level of the script. This anonymous part of the trace indicates where the script execution starts. The error occurred at line 12, column 1 of thetest.jsfile. This is where themain()function is called directly from the script.

This is called a stack trace. The throw new Error() statement prints the entire stack trace, which unwinds back through the series of function calls that were made leading up to the point where the error occurred. Each function call is recorded in reverse order, starting from the function that directly caused the error and going back to the initial entry point of the script.

This trace of function calls, along with their corresponding file paths and line numbers, provides developers with a clear trail to follow. It aids in identifying where and how the error originated.

This is exactly what we want to know where was the logger.error and the other methods are being called from.

Getting the callee name and the line number

How can we use the information above to obtain the line number from the client's code? Can you think about it?

Let's add the following in our #log method of the Logger class:

// file: lib/logger.js

class Logger {

...

async #log(message, log_level) {

if (log_level < this.#config.level || !this.#log.file_handle.fd) {

return;

}

/* New code inserted */

let stack_trace;

try {

throw new Error();

} catch(error) {

stack_trace = error.stack;

}

console.log(stack_trace)

/* New code ends */

await this.#log_file_handle.write(log_message);

}

...

}

Try to execute the test.js file.

// file: test.js

const { Logger } = require("./index");

async function initialize() {

const logger = Logger.with_defaults();

await logger.init();

return logger;

}

async function main() {

let logger = await initialize();

logger.critical("Testing");

}

main();

This outputs

Error

at Logger.#log (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/lib/logger.js:98:19)

at Logger.critical (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/lib/logger.js:141:18)

at main (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:12:12)

Awesome. We now know who invoked the function. There are 4 lines. The important piece is on the last line.

at main (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:12:12)

This is where we called logger.critical('Testing'). However, you may think - "Yeah fine, it's always the last line". No, it is not. Let's add two nested functions in test.js

// file: test.js

...

async function main() {

let logger = await initialize()

nested_func(logger)

}

function nested_func(logger) {

super_nested(logger)

}

function super_nested(logger) {

logger.critical('Testing')

}

...

After executing node test.js we get the following output.

Error

at Logger.#log (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/lib/logger.js:98:19)

at Logger.critical (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/lib/logger.js:141:18)

at super_nested (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:20:12)

at nested_func (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:16:5)

at main (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:12:5)

However, this time, there are two more lines. If you read the stack trace from the bottom to the top, you can understand the sequence of steps that led to the error. The most useful information is not actually at the very bottom, but rather on the fourth line (including the "Error" line at the top of the stack trace).

at super_nested (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:20:12)

The 4th line will always be the one that invoked the method. Which is the line directly below the call to Logger.critical. Isn't that what we need?

A more ergonomic way

Looking at the code we just wrote in our Logger.#log method, it seems poorly written, making it hard to understand our desired outcome. Additionally, why are we throwing an Error? Someone unfamiliar with our code might consider it redundant and remove it.

We can make it even better by creating a helper method that extracts essential information from our stack trace.

Add a new function in the lib/utils/helpers.js file

// file: lib/utils/helpers.js

function get_caller_info() {}

module.exports = {

check_and_create_dir,

get_log_caller, // Add this!

};

We are going to get our stack trace in a shorter and more efficient way. Here's what we're going to do

// file: lib/util/helpers.js

function get_caller_info() {

const error = {};

Error.captureStackTrace(error);

const caller_frame = error.stack.split("\n")[4];

const meta_data = caller_frame.split("at ").pop();

return meta_data;

}

Error.captureStackTrace(targetObject) is a static method on the Error class that's used to customize or enhance the creation of stack traces when throwing errors. It doesn't throw an error itself, but rather it modifies the target object to include a custom stack trace.

It's designed specifically for capturing stack traces without generating a full error object, which can be helpful when you want to create your own custom error objects and still capture the stack trace efficiently. It directly associates the stack trace with the provided object.

const caller_frame = error.stack.split("\n")[4];

We are extracting the 5th line of the stack trace. Note, it's the 5th line and not 4th like we talked in the previous section. This is because, we introduce one more function get_log_caller, that will also live on the call stack. You can imagine a call stack like this:

get_caller_info

Logger.#log

Logger.critical/Logger.debug etc

user_function // that called `logger.critical`

On the top of the stack trace there's a line that says

Error

So the entire stack trace can be imagined like this:

Error

at get_caller_info line:number

at Logger.#log line:number

at Logger.critical line:number

at user_function line:number // that called `logger.critical`

Right, we only care about the 5th line.

const meta_data = caller_frame.split("at ").pop();

In this line, we are retrieving the part of the string that follows the word "at" followed by a space, as we do not need to include it in our output. Finally, on the last line, we return the necessary metadata to display in the logs.

Using the get_caller_info function

Update the code in the Logger class to use the info provided by the get_caller_info function.

// file: lib/logger.js

class Logger {

...

async #log(message, log_level) {

if (log_level < this.#config.level || !this.#log_file_handle.fd) {

return;

}

const date_iso = new Date().toISOString();

const log_level_string = LogLevel.to_string(log_level)

// add additional info to the log messages.

const log_message = `[${date_iso}] [${log_level_string}]: ${get_caller_info()} ${message}\n`;

await this.#log_file_handle.write(log_message);

}

...

}

Now, we're going to test whether everything works like we expect?

In the test.js file let's write a couple of logs.

// file: test.js

const {Logger} = require('./index')

async function initialize() { ... }

async function main() {

let logger = await initialize()

logger.critical('From the main() function')

nested_func(logger)

}

function nested_func(logger) {

logger.critical('From the nested_func() function')

super_nested(logger)

}

function super_nested(logger) {

logger.critical('From the super_nested() function')

}

main()

The log file shows the following -

[2023-08-19T19:11:51.888Z] [CRITICAL]: main (/Users/ihtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:11:12) From the main() function

[2023-08-19T19:11:51.888Z] [CRITICAL]: nested_func (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:16:12) From the nested_func() function

[2023-08-19T19:11:51.888Z] [CRITICAL]: super_nested (/Users/ishtmeet/Code/logtard/test.js:21:12) From the super_nested() function

This all seems to work pretty well. We now have helpful logs. However, before we start using this logging library in our personal projects, there are a lot of things that need to be taken care of. This includes logging crashes, handling SIGINT and SIGTERM signals, as well as properly utilizing the file_handle.

We'll take care of this in the next chapter.

Note

The code for the entire chapter can be found at the src/chapter_04.3 directory