Chapter 05

HTTP Deep dive

Note

This chapter gives an overview of how the web functions today, discussing important concepts that are fundamental for understanding the rest of the book. Although some readers may already be familiar with the material, this chapter provides a valuable opportunity to revisit the basics.

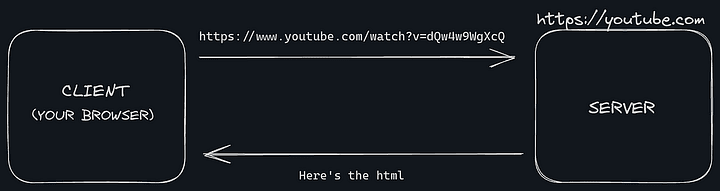

All the browsers, servers and other web related technologies talk to each other through HTTP, or Hypertext Transfer Protocol. HTTP is the common language used on the internet today.

Web content is stored on servers that communicate using the HTTP protocol, often called HTTP servers. They hold the Internet data and provide it when requested by HTTP clients.

Clients ask for data by sending HTTP requests to servers. Servers then respond with the data in HTTP responses.

The message that was sent from your browser is called a Request or an HTTP request. The message received by your browser, which was sent by a server is called an HTTP Response or just Response. The response and the request is collectively called an HTTP Message.

Note

Warning: Don't visit the URL mentioned above.

A small web server

Before introducing more components of HTTP, let's build a basic HTTP server using Node.js.

Create a new project, name it whatever you like. Inside the directory create a new file index.js

// file: index.js

// Import the 'node:http' module and assign it to the constant 'http'

const http = require("node:http");

// Define a function named 'handle_request' which takes two parameters: 'request' and 'response'

function handle_request(request, response) {

// Send the string "Hello world" as the response content

// Do nothing with the request, for now

response.end("Hello world");

}

// Create an HTTP server using the 'createServer' method of the 'http' module.

// Pass the 'handle_request' function as the callback for handling incoming requests.

const server = http.createServer(handle_request);

// Start the server to listen for incoming requests on port 3000 and the host 'localhost'

server.listen(3000, "localhost");

// Alternatively, you can use the IP address '127.0.0.1' instead of 'localhost'

server.listen(3000, "127.0.0.1");

Let's go through the code above in more detail:

const http = require("node:http");

This line brings in Node.js's http module, that provides basic functionality to create HTTP servers.

function handle_request(request, response) {

response.end("Hello world");

}

This function has two input parameters: request (it is the message that comes from the internet) and response (it is the message that we send back to the user). And we're simply sending back a response "Hello world".

const server = http.createServer(handle_request);

We're creating an HTTP server using the createServer method from the http module. The handle_request function is assigned as the callback function that will be called when the server receives a request.

So, whenever there's a new HTTP request, our handle_request function will be invoked, and two arguments request and response will be provided.

server.listen(3000, "localhost");

This line of code starts the server and makes it available at http://localhost:3000.

server.listen(3000, "127.0.0.1");

You can also use the IP address '127.0.0.1' instead of 'localhost' to achieve the same result.

Both localhost and 127.0.0.1 refer to the local loopback address, which means that the server will only be accessible from the same machine it's running on. This is commonly used by developers for testing and debugging purposes.

In fact, it's a best practice to develop and test applications locally before deploying them to a production environment, as it allows for easier troubleshooting and debugging of any issues that may arise.

Starting our web server

To start the web server, we simply need to execute the file index.js. Let's try to run it:

$ node index

## no response, is there something wrong?

You might have noticed that the program didn't exit, like it used to do previously when we ran our logging library or previous code examples. This behavior can be a bit surprising, but it's expected due to the nature of how HTTP servers work.

When we run an HTTP server using http.createServer(), the server is designed to listen for incoming requests indefinitely. It doesn't terminate as soon as the script finishes executing, unlike some other scripts that might perform a single task and then exit.

This is because the purpose of an HTTP server is to continuously listen for incoming HTTP requests and respond to them in real-time. If the server were to exit immediately, it wouldn't be able to fulfill its purpose of serving content to clients.

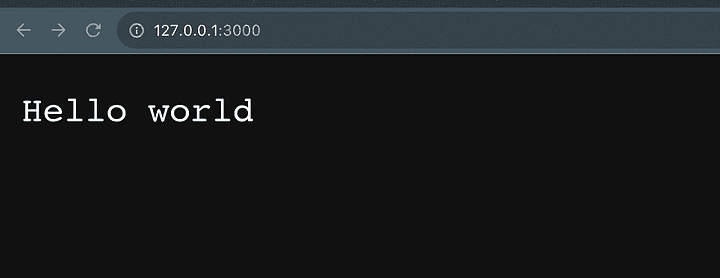

Testing our web server

To see whether our web server is working as we expected, and to see the "Hello world" response back, we need to make a request first. There are certain ways to make a request. We'll take the easy route.

Go to the browser of your choice, and visit the URL http://localhost:3000 or http://127.0.0.1 or localhost:3000 or 127.0.0.1:3000.

Yes, it seems to work correctly. Let's make a request to our server in a different way, to look at all the necessary parts that make up an HTTP request.

Testing with cURL

Open up your terminal, and enter the following cURL command:

$ curl http://localhost:3000

Hello world%

Perfect. cURL is a convenient and a quick way of testing HTTP endpoints. It is easy to use, and do not need to have other HTTP clients running, or your chrome's network tab opened.

Let's modify the cURL request:

$ curl http://localhost:3000 -v

We're specifying the -v argument (also --verbose) which displays more information about the HTTP connection lifecycle. This is the output you get after you execute the command above:

$ curl http://localhost:3000 -v

* Trying 127.0.0.1:3000...

* Connected to localhost (127.0.0.1) port 3000 (#0)

→ GET / HTTP/1.1

→ Host: localhost:3000

→ User-Agent: curl/7.87.0

→ Accept: */*

→

* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse

← HTTP/1.1 200 OK

← Date: Wed, 23 Aug 2023 13:13:32 GMT

← Connection: keep-alive

← Keep-Alive: timeout=5

← Content-Length: 11

←

* Connection #0 to host localhost left intact

Hello world%

That's a lot of stuff to digest. One thing to notice is two different operators that are used - → and ←. The → arrow indicates that this is being sent as a request from the client. Client here refers to the cURL or your terminal. ← indicates that these lines have been received as a response from the server.

Let me walk through this line by line:

Trying 127.0.0.1:3000...

This line is indicating that cURL is attempting to establish a connection to the IP address 127.0.0.1. This IP address is also known as localhost and it refers to the local computer you are currently working on.

The connection is being made on port number 3000, which is a number used to identify a specific process to which data is being sent or received. We'll talk about PORTs in the next chapter.

Connected to localhost (127.0.0.1) port 3000 (#0)

This means the connection to the specified IP address and port has been successfully established. This is great news and means that you can proceed with your task without any further delay.

The (#0) in the message refers to the connection index. This is helpful information, especially if you're making multiple connections at the same time. By keeping track of the connection index, you can avoid any confusion or errors that could arise from mixing up different connections.

→ GET / HTTP/1.1

cURL is sending an HTTP request to the server using the HTTP method GET. The / after the method indicates that the request is being made to the root path, or the root endpoint of the server.

→ Host: localhost:3000

This line specifies that the cURL command is setting the Host header on the request, which tells the server the domain name and port of the request.

→ User-Agent: curl/7.87.0

This line is also part of the HTTP request headers. It includes the User-Agent header, which identifies the client making the request. In this case, it indicates that the request is being made by curl version 7.87.0.

→ Accept: */*

This line sets the Accept header, which tells the server what types of response content the client can handle. In this case, it indicates that the client accepts any type of content.

→

This line indicates the end of the HTTP request headers. An empty line like this separates the headers from the request body, which is not present in this case because it's a GET request. We'll talk about POST and other http verbs/methods in the upcoming chapters.

Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse

This is an internal log message from curl and doesn't have a direct impact on the request or response interpretation. It's related to how curl manages multiple connections in a session.

← HTTP/1.1 200 OK

This line is part of the HTTP response. It indicates that the server has responded with an HTTP status code 200 OK, which means the request was successful. Again, we're going to understand HTTP status codes in the next chapter. For now, it's enough to think that any status code in the form 2xx, where x is a number, means everything is fine.

← Date: Wed, 23 Aug 2023 13:13:32 GMT

This line is part of the HTTP response headers. Important thing to note, this is the header set by the server, and not the client. It includes the Date header, which indicates the date and time when the response was generated on the server.

← Connection: keep-alive

This line is part of the response headers and informs the client that the server wants to maintain a persistent connection, and re-use the connection for potential future requests. This helps with the performance.

← Keep-Alive: timeout=5

This line, also part of the response headers, specifies the duration of time (5 seconds in this case) that the server will keep the connection alive if no further requests are made.

← Content-Length: 11

This line indicates the length of the response content in bytes. In this case, the response body has a length of 11 bytes.

←

This line marks the end of the response headers and the beginning of the response body.

Connection #0 to host localhost left intact

This line is a log message from curl indicating that the connection to the server is being left open (intact) and not closed immediately after receiving the response. It could potentially be reused for subsequent requests.

Hello world%

This is the actual response body returned by the server. In this case, it's a simple text string saying "Hello world". The % is nothing to worry about. It indicates that the response doesn't ends with a \n character.

Now that we understand what are the basic components of the request and the response, let's understand these components in more detail, in the next chapter