Chapter 05

User agents

A user agent is any software client that sends a request for data or information. One of the most common type of user agent are the web browsers. There are many other types of user agents as well. These include crawlers (web-traversing robots), command-line tools, billboard screens, household appliances, scales, light bulbs, firmware update scripts, mobile apps, and communication devices in various shapes and sizes.

It's worth noting that the term "user agent" doesn't imply a human user is interacting with the software agent at the time of the request. In fact, many user agents are installed or configured to run in the background and save their results for later inspection or to only save a subset of results that might be interesting or erroneous. For instance, web-crawlers are typically given a starting URL and programmed to follow specific behavior while crawling the web as a hypertext graph.

In our cURL response, we have the user-agent listed on this line:

→ User-Agent: curl/7.87.0

Here, the user-agent is the cURL command line program that we used to make the request to our server. But, it get's more strange when you make a request from a browser. Let's see that in action.

User-Agent can be weird

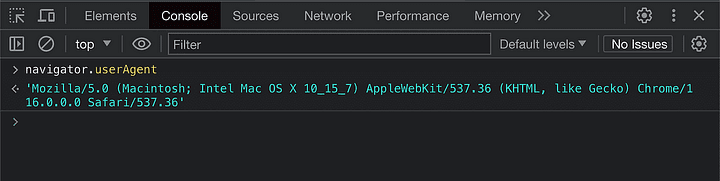

Open chrome or any browser of your choice, and open the web console using Command + Option + J on a mac or Control + Shift + J on windows or linux. Type the following command in the console and press enter:

navigator.userAgent;

This outputs:

Ha, such a weird looking string isn't it? What are 3 browsers doing there? Shouldn't it be only Chrome?

This phenomenon of "pretending to be someone else" is quite prevalent in the browser world, and almost all browsers have adopted this strategy for practical reasons. A great article that you should read if you're interested is the user-agent-string-history.

For instance, let's examine the example in question:

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/116.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

It is a representation of Chrome 116 on a Macintosh. But why is it showing Mozilla, even though we are not using it?

Why does a browser behave that way?

The answer is simple. Many websites and web pages are designed to identify which browser is visiting the page, and only deliver certain features if the browser is Chrome/Mozilla/... (although this is a BAD programming practice, (we'll get to it in a bit) it happens, especially in the early days of the Internet). In such cases, if a new browser is released and wants to provide the same features for that page, it must pretend to be Chrome/Mozilla/Safari

Does that mean that I cannot find the information I need from the User-Agent header?

Not at all. You can definitely find the information you need, but you must match the User-Agent precisely with the User-Agent database. This can be a daunting task because there are more than 219 million user agent strings!

Like I told earlier, checking the type of browser to do things separately is a very bad idea. Some reasons include:

- Malicious clients can easily manipulate or spoof user agents, causing the information provided in the user agent string to be potentially inaccurate.

- Modern browsers often use similar user agent structures to maintain compatibility with legacy websites, making it difficult to accurately identify specific browsers or features based solely on user agents.

- The rise of mobile devices and Internet of Things (IoT) devices has led to a diverse range of user agents, making it challenging to accurately identify and categorize all types of devices.

- Some users might switch user agents to access restricted content or to avoid being tracked, resulting in unexpected behavior when making decisions based on user agent data.

- Many alternative and lesser-known browsers and user agents do not follow standard patterns, so relying solely on well-known user agents could exclude valid users.

- Tying application behavior too closely to specific user agents can hinder future updates or improvements and complicate the development process by requiring constant adjustments.

You can find a very detailed explanation on why this is bad here - Browser detection using the user agent and what alternate steps you could take in order to create a feature that's not supported on some browsers.